Why do Bible adaptations often become controversial?

Quick Answer:

Religion is a delicate subject to adapt for the big screen. In addition to telling stories that some consider historical fact while other interpret as legend or metaphorical literature, the Bible includes many books with multiple authors that allow space for various interpretations. While many believers of Christianity and Judaism look to parts or the whole of the Bible as a rigid source of belief, the historical veracity of most of the words can be neither proved nor denied, and many disagree as to whether Biblical authors even intend to be read historically, literally or symbolically. Cinematic interpretations of the Bible reflect the individual visions of the filmmakers, as well as sometimes the studios or religious groups driving the adaptation. Just as the filmmakers interpret the Biblical excerpt that they’re adapting, audiences also interpret the film and hold up it to their personal measures of accuracy and value. They may compare these adaptations to their ideas of “the truth,” or they may view them as works of art inspired by but separate from the Bible. Given how difficult the complex and ambiguous language in the Bible is to definitively comprehend, any attempt to film the Bible must inevitably provoke a wide variety of audience reactions.

Even a film’s choice of genre or target audience becomes controversial in how tales of the Bible are depicted. For example, The Prince of Egypt (1998) and The Miracle Maker (2000) contain animated adaptations of the Bible that is targeted specifically towards children. The film featured dark elements of violence and death present in the Biblical stories, but here they have been adjusted for a more child-friendly audience. Both films provide children with an educational understanding but, at least according to older audiences and their personal beliefs, the films were criticised for being inaccurate.

On the other end of the scale is The Passion of the Christ (2004), the top-grossing R-rated movie to date as well as the highest-grossing religious film and film not in the English language. Far from softening dark aspects of the Bible, The Passion of the Christ polarized audiences by focusing in gory detail on the physical torture and pain Jesus endures in his final days (from the Lain “passionem,” meaning suffering or enduring, in Christianity the “Passion of Christ” refers to the period between Jesus’ entrance to Jerusalem and his crucifixion on Mount Calvary). Retelling the story of Jesus is a sensitive topic for both Christians and non-Christians, and audiences reacted with unsurprising division in their reactions to The Passion of the Christ. Upon release in February 2004, the film received mixed reviews from critics. Some praised Jim Caviezel’s performance as Jesus Christ, the mise-en-scéne and music. Others criticized the film’s use of extreme violence and accused it of anti-Semitism. Asked whether his movie portrays Jews in a disparaging light, director Mel Gibson gave the ambiguous response, “It’s not meant to. I think it’s meant to just tell the truth. I want to be as truthful as possible.” Gibson as a director known for depicting extreme violence in historical dramas, but critics of The Passion of the Christ felt the emphasis on the details of Christ’s physical suffering and torture served to vilify Jews and obscured any other message he intended to send.

In recent cinema, the list of Biblical film adaptations has become shorter. Box office records and today’s audience dictate that fantasy cinema is now taking control of mainstream Hollywood. More recent examples of Bible-inspired films include fantasy elements such as basic plot trends, such as character names and story outline but are adjusted to meet the visual requirements of today’s fantasy-dominant Hollywood. With the exception of The Passion of the Christ, Box Office Mojo statistics show that Christian films have financially slumbered on theatrical release. This specific list, however, includes The Chronicles Of Narnia franchise among the top with a box office total of over $1.5 billion worldwide between the three instalments. Despite not strictly being about religion or the Bible, the fantasy-adventure series does contain hidden references to it. One such example is the character of Aslan, whose sacrifice and resurrection in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005) is a parallel to Jesus Christ. Fantasy is quite a predominant genre today in terms of religious representations, and this particular example reflects on how accuracies of certain Biblical stories are somewhat dismissed by the fictional context and enhances audience’s enjoyment further.

Another way of looking at fantasy in its representation of religion is how the Bible interprets it as historical events. It may be considered fantasy today but from the Bible’s complex interpretation, certain elements could still arguably be history. This unique idea of historical-fantasy has drawn controversy surrounding certain religious adaptations. For example, Noah (2014) is a Bible-inspired drama by visionary director Darren Aronofsky. With Russell Crowe leading the cast, Noah depicts the story of the infamous Ark that cleanses the world’s evil via flood. This is a clear narrative elements considered common knowledge. However, it is also an “inspired” version of the story, and the complexity of how this is portrayed has been controversial. Particularly the involvement of The Watchers, a group of fallen angels bound as stone giants with six arms, sparked controversy. Some have also criticised the visuals, while some consider that they provide an honest representation of how the Beginning occurred; particularly in the creation sequence.

A similar film that applies adjusted elements that meet the production scale of today’s industry is Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) by Ridley Scott. The film performed poorly at the box office and alongside it was still a string of mixed reviews and controversy. The film involves the well-known prophet Moses, but his story from the Bible appears different. In fact, The Independent claimed Exodus: Gods and Kings was banned in Egypt, its country setting, for “historical inaccuracies”. Such comments included - “the country’s censors were unimpressed with the film’s claim that an earthquake sparked the famous Parting of the Red Sea, rather than a divine miracle, and another suggesting that Jews built the Pyramids.” Far overshadowing the movie was its “whitewashing” controversy, as many criticized the casting of white Hollywood actors Christian Bale and Joel Edgerton as Moses and Rameses, while ethnic minority actors took on supporting roles.

However, looking further back, have Biblical adaptations always been responded to in this negative way? Perhaps not. In pre-1970 films, Bible stories were represented as epic cinema, a style of filmmaking at a mass budget and production scale with a variety of starring actors. For example, The Ten Commandments (1956) stars Charlton Heston in the lengthy 220-minute classic featuring the story of Moses who leads the Hebrew people from enslaved Egypt to the Promised Land. The film’s production scale was so significantly large that it was Hollywood’s most expensive feature at the time, which may have distracted the audience’s questioning of the Biblical accuracies. Being a remake of the 1923 silent film of the same name (and same director B. DeMille), The Ten Commandments featured ground-breaking production values that distracted from an audience’s clinical observations. Film production was still an experimental phase at the time and the large storytelling scope of Biblical stories became a clinical source for it; therefore, making them less controversial and more appreciative for viewers to enjoy.

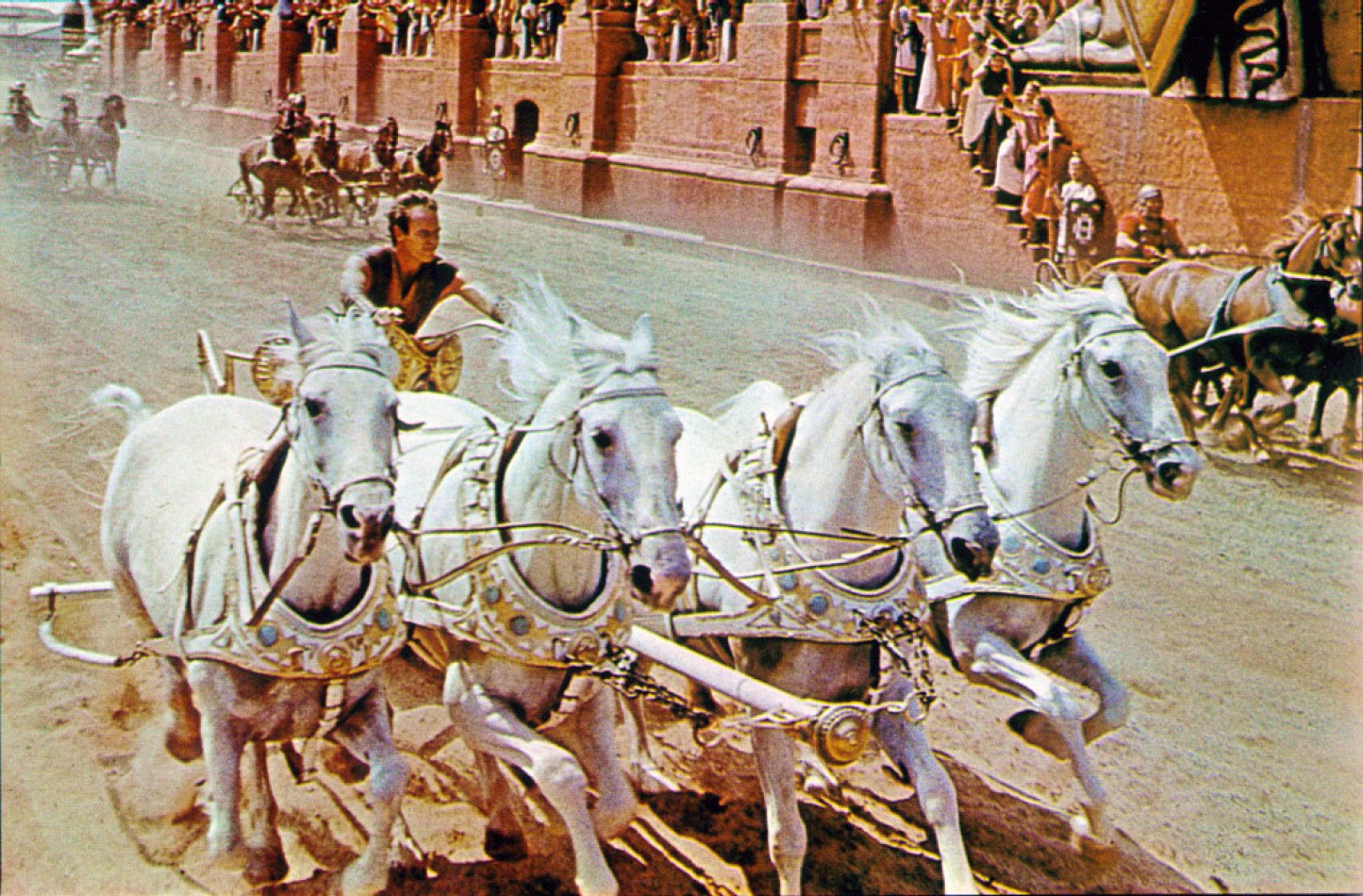

Another example of this is Ben-Hur (1959). It is not a Biblical epic as such, but it is set throughout the time of Jesus Christ. Also starring Charlton Heston in the leading role, the film drew low religious controversy as it was released in an era considered popular for religious epics. The film was particularly praised for its production techniques, especially during the infamous chariot race sequence. In addition to strong critical responses, allocates have also been predominant for these classic religious and Biblical adaptations. Ben-Hur, in particular, gained an astounding 11 Academy Award wins, a record now tied with Titanic (1997) and The Lord Of The Rings: Return Of The King (2003). Like The Ten Commandments, the ground-breaking technical values of Ben-Hur appeared as a distraction from analogies concerning Biblical accuracy.

50 years later, however, Ben-Hur has also been remade with a release date of August 2016. During production in 2015, the film already aroused controversy. A Guardian report states that the Italian authorities have banned production at Rome’s Circus Maximus for “technical reasons.” It was the location of where the 1959 chariot race was shot, and the mayor’s office commented on recreating it. They said that “the aim of the city administration isn’t so much to raise revenue in exchange for the use of public space, but to give back to Rome the role of being a big international set, which is in our history and our tradition.” As a result, production schedule was eventually altered to a studio-based set. The point being made here is that Biblical adaptations for contemporary audiences appears more controversial. They are taken more seriously with one possible reason being that today’s generation are losing interest or faith in their religion, or it could be the growing technicalities of film production and strategies of distribution that are misleading.

The question remains about adaptations of the Bible – why do the more recent films become more controversial than the older ones? It might be the change in how the Bible has been represented based on technological advancements and production scales. Or it could be that today’s audience may be less appreciative of Biblical adaptations and instead prefer references to it. Considering this, the Bible is still a sensitive subject that sparks reactions – usually controversial. Like general cinema, however, the Bible is a source for debate. In fact, Quentin Tarantino has claimed that “cinema is the new church”, implying that it is a new medium with the influential power in people expressing opinions, much like the way in which people interpret their beliefs from the Bible. One way to look at Bible stories is an adaptation from a book, while another is to look at Bible stories as visual recreations of history. Therefore, it is primarily down to the audience’s reaction and each individual’s opinion as to how these Bible adaptations are represented.