How is the Harry Potter Universe an Alternate Existence of British Society and Education?

In a world of mainstream film franchises, we tend to identify a particular series with the country that produced it, taking that filmic universe to represent and epitomize the place where it was originated or filmed. The US has Star Wars (among many); New Zealand has Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit; Australia has Mad Max; Sweden has the Millennium trilogy, and France has the artful Three Colors trilogy by Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski. Many of these franchises that we link with national identities are set in fantasy worlds, far from a realistic portrayal of their nations of origin, but sometimes offering what feels like an alternate existence for each country that retains the national character.

Harry Potter is a crucial example of this phenomenon, as it is arguably considered the United Kingdom’s landmark franchise. Although the adaptations of J.K. Rowling’s series of novels were distributed by American studios, the franchise revolves around central aspects of British culture. Practically the entire cast of Harry Potter features all known British actors, some of whom have crucial roles or mere cameos. These include the late Richard Harris (Dumbledore no. 1), Michael Gambon (Dumbledore no. 2), the late Alan Rickman (Snape), Ralph Fiennes (Voldemort), Maggie Smith (McGonagall), Emma Thompson (Trelawney), David Thewlis (Lupin), Gary Oldman (Sirius), Jim Broadbent (Slughorn), Kenneth Branagh (Lockhart), Robbie Coltrane (Hagrid), Warwick Davis (Flitwick, Griphook), Helena Bonham Carter (Bellatrix), Julie Walters (Mrs Weasley), Brendan Gleeson (Mad-Eye), Timothy Spall (Wormtail), Julie Christie (Madame Rosmerda), the late Richard Griffiths (Uncle Vernon), Imelda Staunton (Umbridge), David Tennant (Barty Crouch Jr), and Bill Nighy (Scrimgeour), among others.

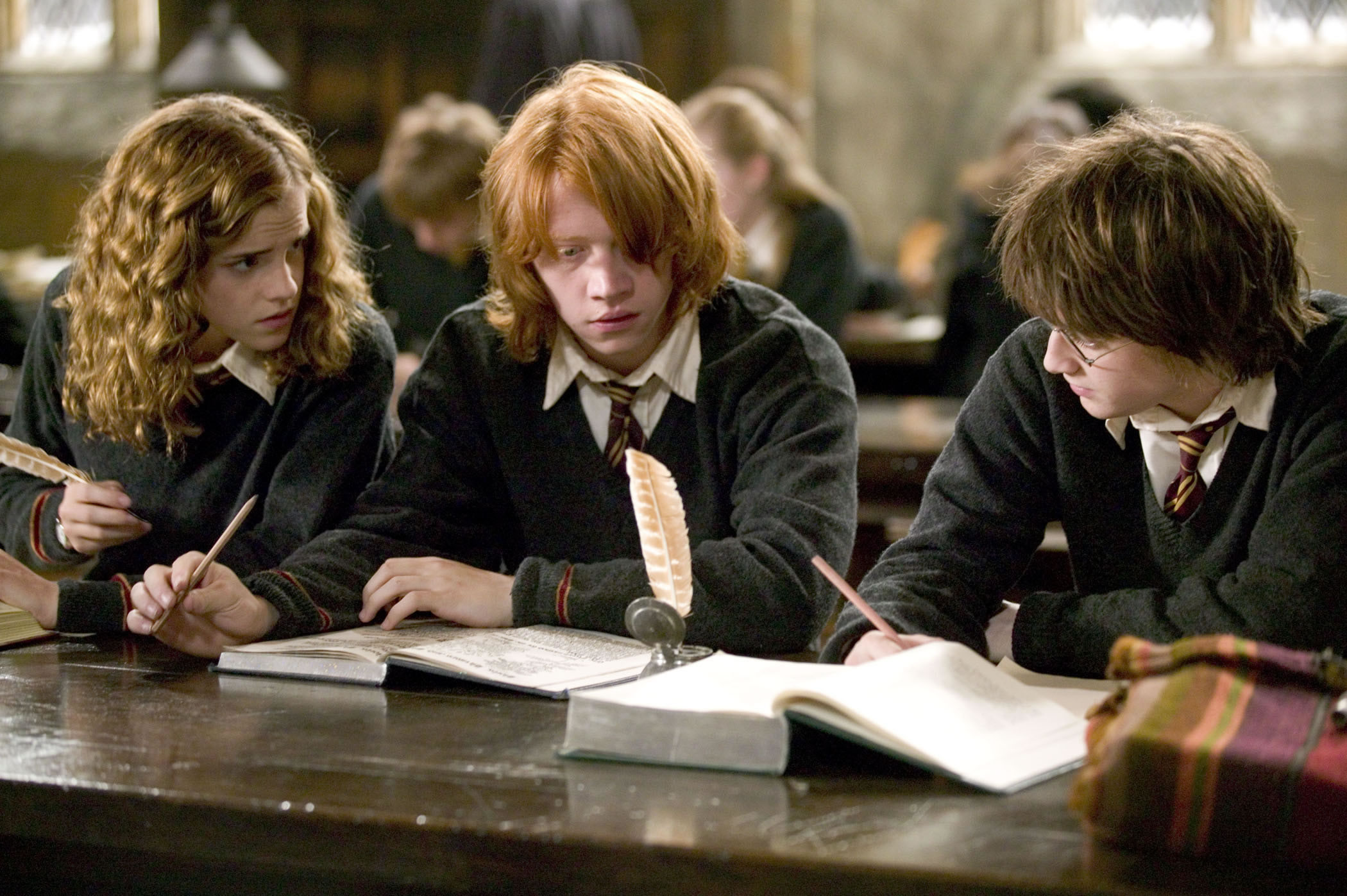

In addition to this abundance of establish British stars, the rising youngsters at the center of the movie (Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, Emma Watson, Tom Felton, Bonnie Wright, etc) have become household names, especially in Britain. The cultural significance of the franchise has altered how audience connections meet with and grow with young characters in film. Radcliffe, Grint and Watson started The Philosopher’s Stone in 2001 from the age ranges of 11-13 years old and concluded Deathly Hallows: Part II in 2011 from 21-23 years old. Viewers who were born from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s grew up literally alongside the young stars as the franchise continued. Witnessing the three grow up on the screen allowed us to connect further with the alternate existence of Britain which is the Harry Potter franchise.

Harry Potter is all about magic. The films feature magic at its best and worst. More significantly, watching the eight films is also a magical experience—we not only watch on-screen magic but we also feel it (emotionally) reflecting off the screen. The Harry Potter films, in a nutshell, offer an escapist replica of British society that may have its dangerous, dark moments but is full of bright, clever creations and ends with the closure that, in the end, good triumphs over evil.

Considering that Harry Potter features multiple fictional locations such as Hogwarts, Godric’s Hollow, the Leaky Cauldron and Diagon Alley, the series (in addition to numerous sets) uses city and countryside landscapes of the United Kingdom. The Death Eaters’ attack on central London in Half-Blood Prince (2009) establishes the endangerment of “normal” British society, especially as this attack also occurs in Diagon Alley. When outside of Hogwarts and school, the students must exhibit the lifestyles of Muggles, a formal term for “non-magic” citizens, as performing magic under a certain age is illegal. Harry lives with his maternal Aunt, Uncle and cousin in Surrey. We see them all together in opening scenes of British suburbs (except in Goblet Of Fire, Half-Blood Prince and Deathly Hallows: Part II), but each time we see a moment of magic that intervenes, and we are whisked off from normal British life to an alternate world. Hagrid arrives and gives Harry’s cousin Dudley a pig’s tail in The Philosopher’s Stone; Ron and his twin brothers arrive in their father’s flying car to rescue Harry from his bedroom window in The Chamber Of Secrets; an eccentric triple-decker bus reaches Harry’s location near a park and takes him to the Leaky Cauldron in the Prisoner Of Azkaban; Harry is rescued by members of the Order who fly to Grimmauld Place in Order Of The Phoenix. The Order act likewise in Deathly Hallows: Part I to protect Harry from an assassination attempt before he goes into hiding. The threat from Lord Voldemort, therefore, takes place beyond the borders of magic and wizardry but in general British society, and we see our heroes become part of it. The characters are still often in normal British sites. Perhaps the most obvious location that transitions from non-magic environment to magic is King’s Cross Station, where there is a magical transportation to a secret platform called 9 ¾. From this platform, a steam train takes students to Hogwarts before viewers escape to an enchanting lifestyle of magic.

Despite that Hogwarts specialises in practises of Witchcraft and Wizardry, it is still considered an all-around school. The most crucial evidence that Harry Potter presents an alternate existence of Britain is the striking way in which Hogwarts’ educational regulations and structure resemble British schools. However, in the story, British schools are re-imagined within a fantasy and imaginative context. As in traditional British education, the Hogwarts students all have a summer holiday (which is shorter than the US summer holiday) before returning soon after, clearly in September. Apart from Deathly Hallows: Part II, each of the films follows a chronological structure of British academic years from September to Halloween and the Christmas holidays in December, ending after the new year blossoms into spring and finally summer. In this sense, the chronological structure of the British academic year simultaneously occurs alongside the events. Each school year is an experience, after all, and Harry Potter portrays them with a beginning, middle and end. The Hogwarts teachers also use many of the standard educational language that is well-known to British pupils. Professor Dumbledore, for instance, discusses the “term,” a British word used for “semester,” and Professor McGonagall uses “detention” to punish students for wrongdoings, whether in or out of class. Of course, since we are in the magical world of Harry Potter, the punishments are more severe and dangerous.

Within Hogwarts, the students are taught specialist subjects, many of which do resemble our normal school subjects with a fantasy element addition. Instead of Chemistry, wizarding students take Potions. Instead of Biology, they learn Herbology and Care of Magical Creatures. Instead of Religious Studies, they have Muggle Studies. Instead of Physics, they study Divination. Instead of History, they can choose Ancient Runes or a general History of Magic. Instead of Physical Education, they take Flying and Defense against the Dark Arts. And instead of Maths, they can master Arithmancy, which focuses on the magic of numbers.

The way these courses are structured strongly resembles the setup of British secondary education. Some classes are only taught in First Year, others are compulsory throughout all seven years, and other are optional for students to specialise in during their final years. Even Britain’s secondary exams, called GCSEs, are re-envisioned as O.W.L.s (Ordinary Wizard Levels) in the Harry Potter universe. Harry and his classmates take them in their fifth year, and ordinary British students normally take their GCSEs in fifth year, too. O.W.L.s are depicted as insignificant to the real magic at Hogwarts, as some may consider GCSE’s irrelevant in the future to, for example, one’s higher education qualifications. (At the end of Hogwarts, the students face their N.E.W.T.s, or Nastily Exhausting Wizarding Tests.)

Outside of classrooms, activities in the Harry Potter world are represented as variations on British society’s most popular pasttimes. Football, for instance, is replaced by Quidditch, which is a popular Wizarding sport using broomsticks. Even the team positions have similiarities, as Quidditch involves a defending Keeper, central Beaters and the attacking Seeker and Chasers. Due to its popularity, there’s even a World Cup comprised of competing teams from different nations across the world. Introduction to the Quidditch World Cup is one of the first ways we learn that the wizarding world is global, not only in the United Kingdom.

As the wizarding world is global, they also grapple with many of our world’s class and race issues, although they are reflected in different wordings and specific conflicts. J.K. Rowling creates racial tension between wizards based on the “purity” of their blood (meaning what proportion of their ancestors had the ability to do magic). “Pure-Blood” families have a full ancestral past of wizards. These families include the Weasleys (including Ron, Fred, George and Ginny) and the Blacks (Sirius Black, Bellatrix Lestrange). “Half-Blood” wizards are represented similar to mixed race with parents each from Wizardry and Muggle backgrounds. Examples include Harry Potter, Albus Dumbledore, Severus Snape and Lord Voldemort. Thirdly, “Muggle-borns,” who are called by the offensive term “Mudbloods” by racists and especially Voldemort’s Death Eaters, come from non-wizard parents. They include Hermione Granger, Moaning Myrtle, Colin Creevey and Harry’s mother Lily Potter. The differentiations among social groups have a clear racial underpinning, while they are compounded by financial inequalities - in the wizarding world, too, no one is free from the pressures of money.

Even the food and drinks that students eat at Hogwarts resemble our everyday meals (toast, cereal, fruit juice, chicken, profiteroles, etc), although some fictional beverages contain a magical ingredient. For example, Bertie Bott’s Every Flavour Beans are candy sweets which include the tastes of practically anything. Weasley twins Fred and George also have their own snackboxes with a bewitched aftereffect, such as pastels that causes the consumer to vomit. Others, though, are an alternate beverage from that of foods and drinks eaten by Muggles. Butterbeer is a very slightly alcoholic drink served in wizard pubs, specifically in Hogsmeade. Following the conclusion of final film in 2011, Butterbeer has since become a real drink that can be consumed at the Warner Bros Studio Tour near London. The point remains, though, that even if these products are based within a fictional world, they bear a strong symbolic resemblance to the everyday objects and rituals that define how British citizens live.

On that fateful day of when J.K. Rowling first came up with Harry Potter on a train, did she intentionally want the series to be an alternate version of British society? It’s impossible to know, but the ties that combine Harry Potter’s fantasy universe with our normal civilized society could be a large contributing factor to the franchise’s enormous success, as audiences can identify elements of our everyday life in an escapist world. The magical properties and characters seen in Harry Potter allow viewers to escape their painful realities while simultaneously enjoying universal aspects of the United Kingdom culture as it is lived.